Two Inches: The Distance Between Dinner Prep and a Sciatica Flare

That’s all it can take for a “normal” countertop to turn your routine into a delayed nerve flare. The body doesn’t panic during the chop—it bills you afterward.

If your sciatica-like symptoms spike after cooking, it’s often the quiet forward lean: ribs drifting toward the board, shoulders inching forward, and the low back bracing to stabilize. Keep guessing, and you lose more than comfort—you lose evenings, sleep, and the ability to trust your kitchen routine.

An elbow-height cutting board riser is a simple way to raise the surface (usually 2–4 inches) to reduce trunk flexion while keeping shoulders relaxed and wrists neutral. It’s cheaper than replacing counters—and safer than “pushing through” until the leg goes electric.

This approach uses a short, repeatable test: start at +2 inches, pass a no-wobble safety check, and judge success by how you feel 10–60 minutes after you’ve finished.

The Assessment

The 60-second elbow-height check to find your baseline.

The Setup

Riser options that provide a rock-solid, wobble-free surface.

The Strategy

A 7-day micro-adjustment protocol to lock in your perfect height.

Table of Contents

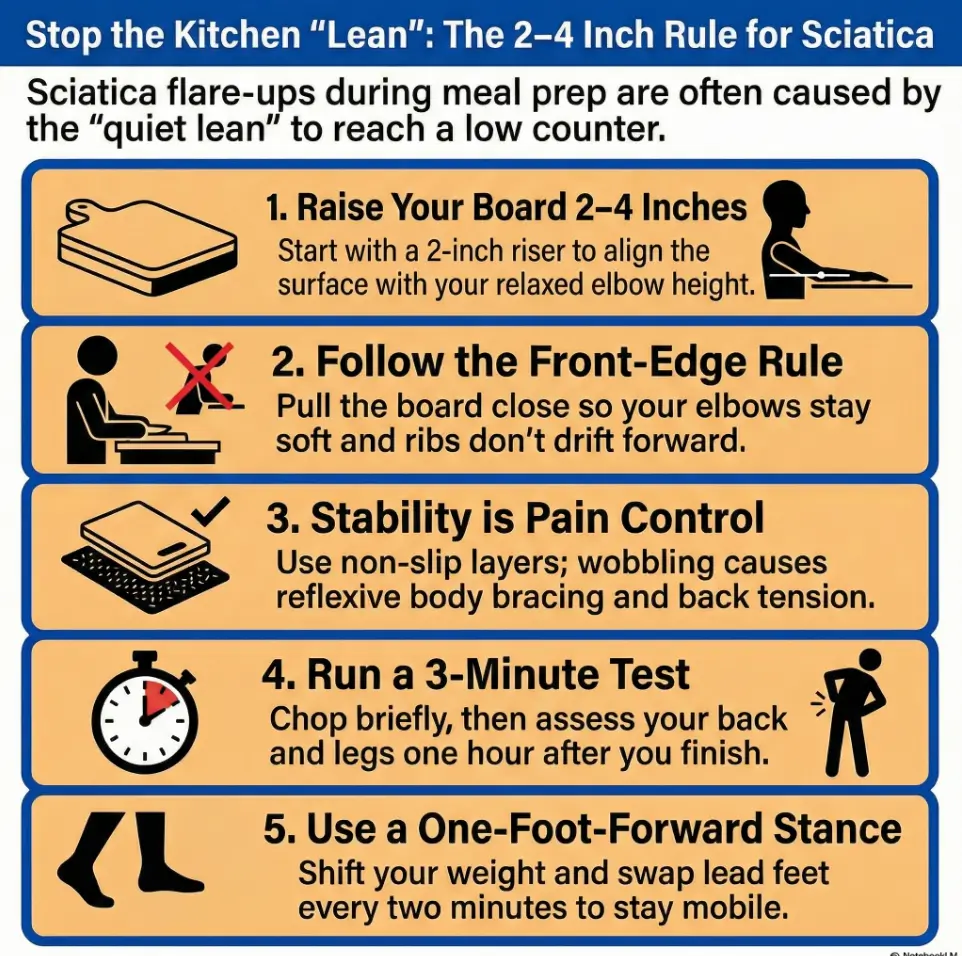

2–4 inch rule: why sciatica hates “just a little lean”

The trap with kitchen pain is that it’s quiet. You’re not sprinting or deadlifting. You’re just… slicing. And yet the combo of forward reach + time-on-task can turn a normal counter into a flare-up machine.

Here’s what’s usually happening: if the cutting surface is too low, your body “buys” reach by rounding forward. That forward drift can increase tension through the hips and low back, and for people with sciatica-like symptoms, it can be the spark. Not because your counter is evil—because the posture is sticky. You don’t do it once. You do it 200 tiny times during prep.

The 2–4 inch rule is a practical middle lane: raise your board enough to reduce that forward drift, but not so much you hike your shoulders and invite neck/upper-trap misery. For most people, start at +2 inches. It’s the “low drama” adjustment: noticeable relief for the back without instantly punishing the shoulders.

- Low surface → you lean to reach and stabilize

- Lean held for minutes → back/hip fatigue stacks fast

- Too high → shoulder/neck “compensation tax”

Apply in 60 seconds: Put one hand on your low ribs and notice if they drift forward while you “pretend chop.” If yes, your setup is pulling you down.

Confession (the kind you only admit to the cutting board): most of us think we’re standing upright… because our eyes are looking forward. Meanwhile, the hips are quietly sliding back and the ribs are quietly sliding forward. Your back feels it later, in the cruelest form of truth: after dinner—and sometimes it follows you into how to sleep with sciatica decisions that night.

The real villain: forward reach + time-on-task (not your knife)

If you only chopped for 30 seconds, you could do almost anything and get away with it. The problem is meal prep is usually 6–20 minutes of the same shape over and over—hands forward, head slightly down, weight subtly uneven. “Just a little lean” becomes “a little lean for a long time.”

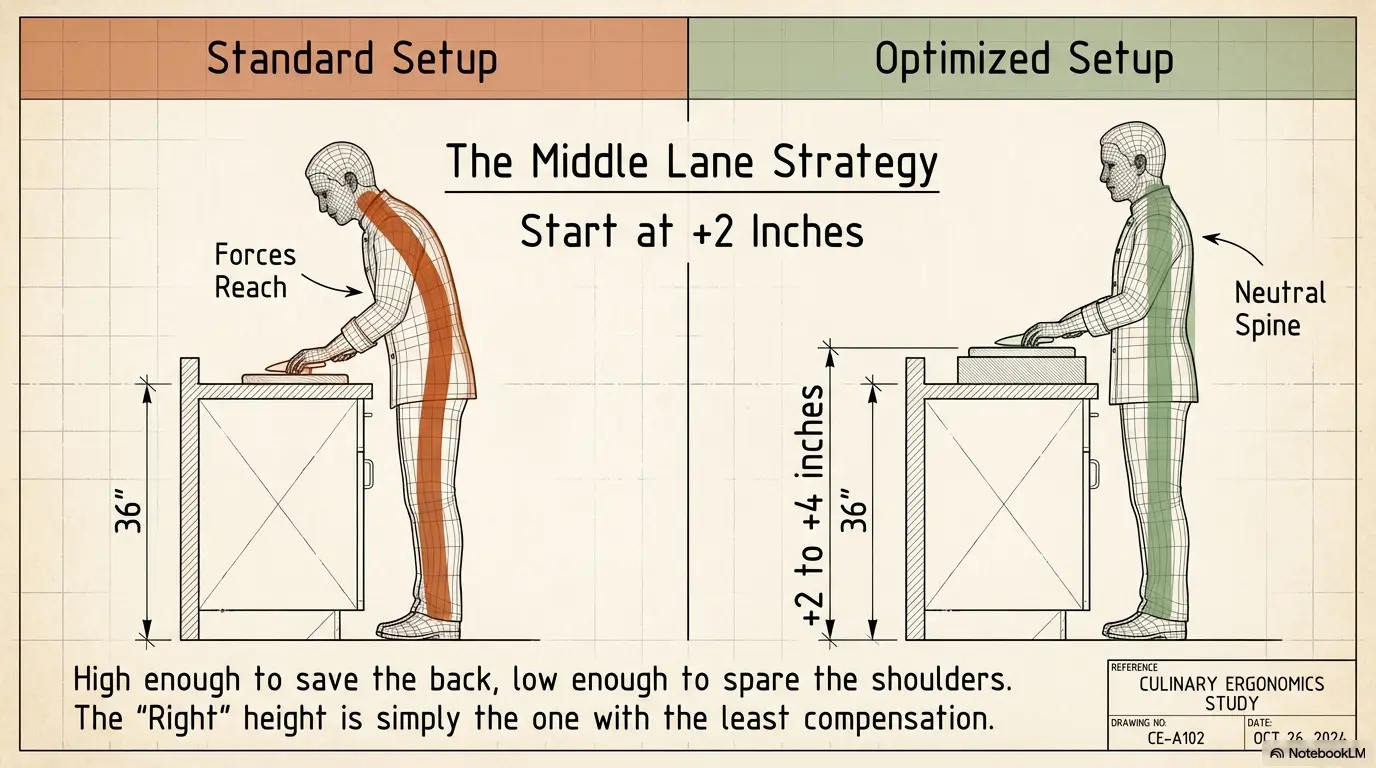

Curiosity gap: why “standard 36-inch counters” can still be wrong for your back

A standard counter height can be perfectly fine for your neighbor and terrible for you. Arm length, torso length, shoulder comfort, and even the thickness of your cutting board all matter. Add a hard floor, thin slippers, and a deep counter that pushes your board back, and suddenly your “standard” station becomes a posture tax you pay every time you chop onions.

Elbow-height check: a 60-second measurement that stops the guessing

You don’t need a measuring tape and a spreadsheet. You need a starting line, then a short test that ends before fatigue. That’s the whole philosophy here: small changes, clean feedback.

Step 1: shoulders down, elbows soft, wrists neutral

Stand where you actually prep. Let your shoulders relax (not “military back,” just calm). Bend your elbows a little so your forearms hover roughly parallel to the floor. Now imagine holding your knife. Your wrists should feel neutral—not bent back, not curled in.

- Green light: shoulders feel heavy and relaxed

- Yellow light: you feel yourself bracing the low back

- Red light: you’re already hiking shoulders to “get up to the work”

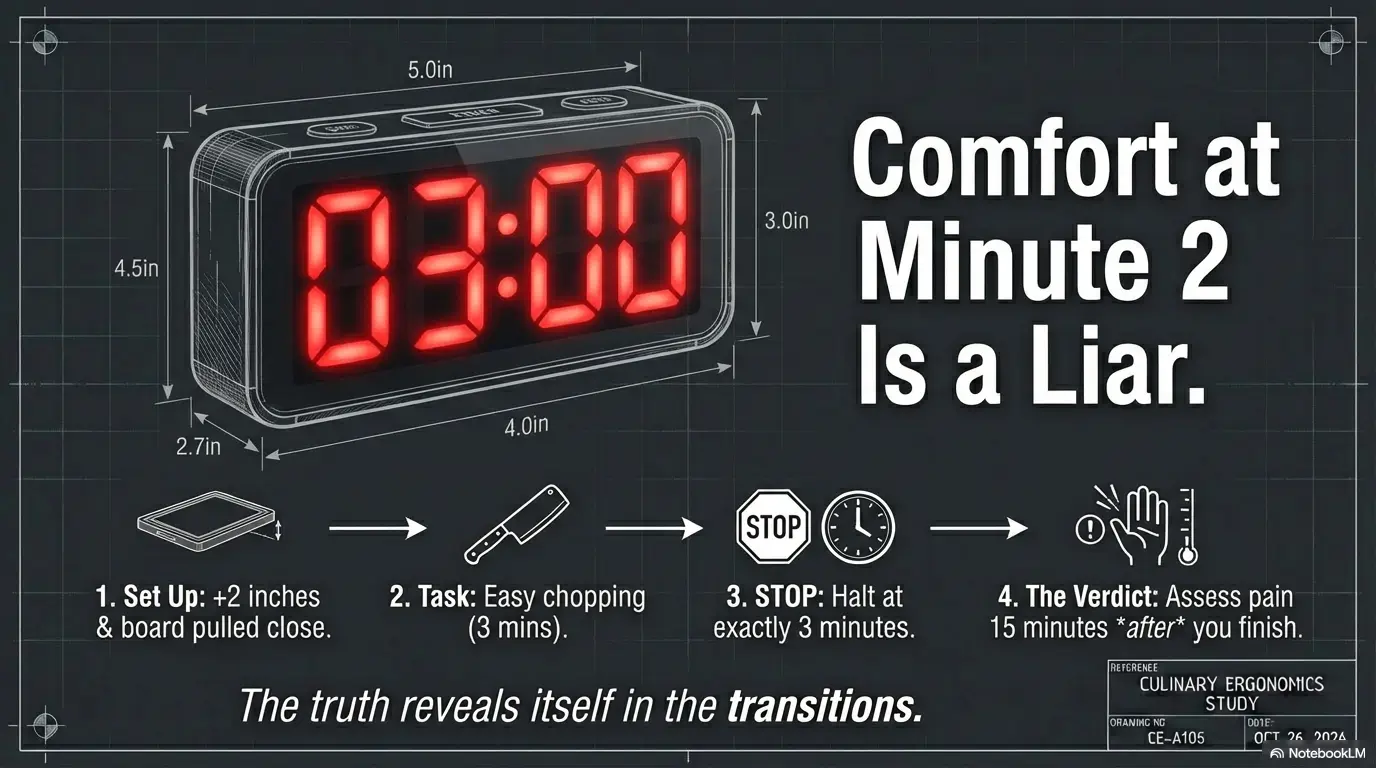

Step 2: test at +2 inches for 3 minutes (then stop)

Start with a +2 inch riser. Then do a 3-minute test with easy chopping (not rock-hard squash). This is intentionally short—because comfort at minute 2 can lie. Your body can “borrow” from the shoulders or low back for a few minutes and pretend it’s fine.

Stop at 3 minutes even if you’re feeling good. Step away. Wait 10–15 minutes. Notice what your leg and back do when you sit down, stand up, or walk to the sink. The truth usually shows up in transitions.

Step 3: adjust by 0.5–1 inch only if symptoms say so

If +2 inches reduces forward lean but you still feel back tightness afterward, add another 0.5–1 inch. If +2 inches makes your neck/upper traps light up, you may need less height (or better board placement and stance). The goal is not “highest is best.” The goal is least compensation.

Show me the nerdy details

Think of your setup like a lever system. Lower surfaces often increase trunk flexion to reach the work area. Small increases in work surface height can reduce the amount of trunk flexion needed for the same task. The “right” height is the one that minimizes compensation: low-back bracing, shoulder elevation, wrist extension, and prolonged forward head posture. That’s why we test briefly and judge by after-effects—not by immediate comfort alone.

- Input 1: Counter height (inches)

- Input 2: Elbow height from the floor while standing relaxed

- Input 3: Cutting board thickness

Apply in 60 seconds: If your board surface is clearly below relaxed elbow level, start with +2 inches before making larger jumps.

A small but important mindset shift: you’re not searching for a “perfect” height. You’re searching for a repeatable default that makes weekday cooking less punishing. The perfect height changes with the knife, the task, and the day your back decides to be dramatic.

Riser choices: three tiers that won’t wobble under a real chop

If you only remember one thing: stability is pain control. Wobble makes you brace. Bracing makes your back and hips angry. And once you’re bracing, you stop moving naturally—which is exactly what a sciatica-prone body hates.

Quick trial (temporary): sheet pan + towel platform (what makes it safe enough)

For a same-day test, use a sturdy sheet pan or baking tray as a base, then a folded towel or non-slip liner, then your board. The goal is not elegance; the goal is controlled height for a short trial.

- Use a wide base (bigger than the board)

- Add a non-slip layer between each surface

- Do a push test with your palms before you introduce a knife

If it shifts with hand pressure, it’s not a platform—it’s a prank.

Semi-DIY (stable): slab/block under board + anti-slip layer

A stable upgrade is a solid slab or block (wood, thick plastic, or a purpose-made riser) with a grippy layer on top and bottom. This is the “set it and forget it” middle path that tends to work well for time-poor cooks.

The key is full contact. Four little points of contact can wobble. A broad, flat surface is calmer. Think “boring and solid” rather than “clever and adjustable.”

Buy option: “adaptive/raised board” features that actually matter

If you prefer buying, prioritize weight, non-slip feet, and a design that’s easy to clean. Fancy features are fine, but the basics decide whether you’ll actually use it on a Tuesday night when you’re tired and hungry.

- Weight: heavier often means less movement

- Feet/grip: stable under lateral pressure

- Cleanability: if it’s annoying to wash, it becomes “special occasion gear”

- Temporary: fastest test, lowest commitment, requires safety discipline

- Semi-DIY: most stable per dollar, easy to keep on the counter

- Buy: clean aesthetics, consistent performance, less tinkering

Apply in 60 seconds: Decide: do you want fast testing tonight or low-maintenance daily use? Pick the tier that matches that answer.

Here’s the part nobody wants to hear: the riser isn’t the whole solution. If your board is still placed too far back, you’ll lean anyway—just from a higher starting point. That’s why placement is not “extra.” It’s the multiplier.

No-wobble rules: the safety checklist your hands will thank you for

Wobble doesn’t just feel annoying. It quietly changes your body strategy: you grip harder, you brace the trunk, and you stop shifting weight naturally. That can turn a “good” height adjustment into a new kind of tension.

Wobble fix #1: shim logic (micro-adjust without re-building your life)

If one corner lifts or clicks, you don’t need to scrap the setup. You need a shim. A thin non-slip pad, a folded paper towel, a purpose-made shim—anything that creates full contact without compressing unpredictably.

Rule of thumb: shim the platform (under the riser), not the board surface. You want the board’s working face to stay flat and reliable.

Wobble fix #2: anti-slip feet vs adhesive feet (what they’re good for)

Anti-slip feet are great for preventing slide on smooth counters. Adhesive feet can be useful, but they can also peel, compress unevenly, or shift over time if they weren’t installed on a clean, dry surface. Whatever you use, do a quick “reality check” weekly: press, push, and confirm nothing has loosened.

Wobble fix #3: edge stop/rail so the board can’t “walk”

This is the underrated move: create a physical stop so the setup can’t creep. Even a simple edge bumper can prevent that slow drift that makes you reach farther over time. When you remove drift, you remove the need to chase the board with your whole spine.

Show me the nerdy details

Stability problems aren’t just about friction; they’re about torque. Chopping introduces lateral forces that can rotate a platform around a small contact point. Increasing contact area, adding high-friction layers, and introducing a physical stop reduces rotational movement. Less movement means less reflexive bracing through the trunk and shoulders—exactly what you want when symptoms flare with sustained tension.

One more operator-grade rule: if you wouldn’t trust the setup with a wet counter and a rushing dinner timeline, don’t trust it at all. Safety isn’t optional when the tool is sharp and your attention is divided.

Board placement: the 2-inch reach mistake that triggers the pain spike

If your board lives even 2 inches too far back, you will reach. And reaching is basically leaning’s sneaky cousin. This is the most common reason someone says, “I raised the board and it still hurts.”

Front-edge rule: keep the board close (reduce reach)

Place the board so the front edge is comfortably close—close enough that your elbows don’t have to straighten to work. If you feel your shoulders creeping forward or your ribs drifting toward the counter, bring the board closer.

- Board too far back → shoulders protract and trunk leans

- Board close enough → elbows stay softer and trunk stays quieter

Sink vs island vs table: best station for short bouts vs long prep

If standing at the counter is a known trigger, consider swapping stations depending on the job:

- Island/counter: best for quick tasks when setup is stable

- Table: can be great for longer prep if it lets you sit or perch

- Sink area: often forces reach and awkward angles—use carefully, especially if you already know washing dishes with sciatica tends to light you up

A small, honest moment: most “kitchen ergonomics” advice forgets that real cooking includes rinsing, carrying, and pivoting. Your setup should make transitions easier, not just chopping. If getting from board to sink makes you twist or lunge, that’s a hidden flare-up trigger.

- Counter height and counter depth (how far you must reach)

- Board thickness and typical food-prep location

- Whether you can keep the board within a comfortable “close zone”

Apply in 60 seconds: Move your board 2 inches closer and re-test a 60-second chop. If it feels instantly calmer, placement is your lever.

Footwork setup: one-foot-forward stance + mat placement (no trapped feet)

Posture cues fail when they’re vague. “Stand up straight” is a motivational poster, not a plan. A better plan is footwork—because foot position controls how your pelvis and trunk manage the task.

One-foot-forward: how to rotate sides without twisting

Use a gentle split stance: one foot slightly forward, knees soft. This reduces the urge to lock both knees and hinge from the low back. Then, every couple of minutes, swap which foot is forward so you’re not loading the same side.

- Left foot forward for 2 minutes

- Right foot forward for 2 minutes

- Micro-break: step back, breathe, reset shoulders

It’s not fancy. It’s just a way to keep your body from becoming a statue—especially if you’re someone who already flares with standing in line with sciatica (same physics, different location).

Mat placement: where it helps—and where it becomes a trip hazard

Anti-fatigue mats can help some people by reducing discomfort from hard floors, but they can also create a “stuck” feeling or a trip edge—especially if you’re stepping back and forth during prep.

- Best placement: centered where your feet actually stand

- Avoid: mats that curl, slide, or force you to pivot on one foot

- Rule: if the mat makes you cautious, it’s not helping

Lightly self-deprecating truth: many of us keep mats that look cute but behave like banana peels. Your back doesn’t care about aesthetics. It cares about predictable footing.

Too low vs too high: symptom-based tuning (the shoulder trap)

The fastest way to mess up a good back fix is to create a new shoulder problem. Height changes shift work between body regions. So instead of guessing, tune by symptoms.

If it’s too low

- Low-back tightness during prep

- Hip hinge fatigue and bracing

- Leg symptoms show up after standing or later that night

- You feel pulled forward toward the board

If it’s too high

- Neck/upper trap burn within minutes

- Shoulders creep upward to meet the work

- Wrists bend back (extension) to control the knife

- Shoulder pinch or “tight collar” feeling

If it’s too low: back tightness, hip hinge fatigue, leg symptoms after prep

If your back feels “held” or you notice a fatigue wave after prep, raise incrementally. But also check placement: a board that’s too far back can mimic “too low” because you’re reaching.

If it’s too high: neck/upper trap burn, wrist extension, shoulder pinch

If your shoulders instantly climb, reduce height or change the task setup: bring the board closer, soften elbows, and consider lowering the food pile so you aren’t working on a mound.

Micro (pattern interrupt): Let’s be honest—‘stand up straight’ is not a plan

A real plan has a test duration, a stop condition, and a next adjustment. Your body deserves that level of respect—especially when it’s already been loud about what it doesn’t like.

Common mistakes: the “helpful” hacks that backfire later

Some hacks feel brilliant for two minutes and then betray you. Let’s save you the betrayal.

Mistake #1: stacking unstable books (wobble + knife risk)

Books compress, slide, and wobble—especially on smooth counters. If you’re going to test height, test it with something that can pass a push test and won’t tilt mid-chop.

Mistake #2: going straight to +4 inches (neck/shoulder flare)

+4 inches can be perfect for some bodies and tasks, but it’s a bold first move. Start at +2 inches, then earn your way upward with symptom feedback.

Mistake #3: marathon prep sessions (duration beats height)

Even a perfect setup can’t save a body that’s asking for a break. If standing time is your trigger, split prep into smaller bouts: 3 minutes, rinse, step away, breathe, return.

Micro (pattern interrupt): Here’s what no one tells you—comfort at minute 2 can lie

Your nervous system can “loan” comfort temporarily. That’s why the test is short—and why you log how you feel later.

Who this is for / not for: fast self-screen before you DIY

This approach is conservative, but it’s still a physical test. Do a quick screen first.

Quick Yes/No

- Yes: Pain spikes with leaning/standing prep and settles with rest.

- Yes: You can walk, change positions, and symptoms are stable.

- No: Progressive weakness, severe numbness, bowel/bladder changes.

- No: Fever, unexplained weight loss, major trauma, or severe unrelenting pain.

Neutral next step: If you’re in the “Yes” group, try the 3-minute test. If you’re in the “No” group, prioritize medical evaluation over DIY changes.

This isn’t about being dramatic. It’s about not missing signals that deserve professional attention. A cutting board riser is a tool, not a diagnosis—and if you’re stuck in constant symptom-checking, cyberchondria with chronic pain can quietly raise your stress baseline in ways that make everything feel louder.

7-day protocol: lock in your best height without chasing perfection

The goal isn’t to “solve your back.” The goal is to find a kitchen default that reduces flare-ups and lets you cook without negotiating with your spine.

Days 1–2: +2 inches, 3-minute test, stop before fatigue

Keep it boring. Do the same simple task each day for consistency—like chopping a few vegetables for dinner. Stop at 3 minutes. Log how you feel one hour later.

Days 3–4: adjust 0.5–1 inch based on symptoms (not vibes)

If back symptoms persist and shoulders are calm, add 0.5–1 inch. If shoulders flare, pull back or refine placement and stance before changing height again.

Days 5–7: batch smarter—shorter sessions, fewer flare-ups

Once height is close, your biggest lever becomes duration. Batch in short rounds: chop 3–5 minutes, pause, reset shoulders, walk 30 seconds, return. If you’re time-poor (most of us are), this is the strategy that survives real life.

| Day | Riser height | Task (3–5 min) | Pain during (0–10) | Pain 1 hr after (0–10) | Notes (neck/shoulder?) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | +2″ | Easy chop | — | — | — |

| 2 | +2″ | Same task | — | — | — |

| 3 | +2.5″ or +3″ | Same task | — | — | — |

| 4 | Confirm | Same task | — | — | — |

| 5 | Lock in | 3–5 min | — | — | — |

| 6 | Lock in | 3–5 min | — | — | — |

| 7 | Lock in | 3–5 min | — | — | — |

Show me the nerdy details

This tracker separates “pain during” from “pain after” because delayed symptom changes can matter. Many people can tolerate a posture briefly, then flare during recovery or later that evening. By keeping the task and duration consistent, you can attribute changes more confidently to height/placement rather than to random kitchen chaos.

Short Story: You start dinner with good intentions. You tell yourself you’ll “just chop quickly,” and suddenly you’re doing the whole week’s vegetables because it feels efficient. Ten minutes in, you notice you’ve stopped breathing normally. Your shoulders are creeping up. Your ribs are leaning forward like they’re trying to taste the cutting board. You finish anyway—because dinner is non-negotiable.

Later, when you stand up from the couch, your leg reminds you that your nervous system keeps receipts. The next day, you do the same meal—but you raise the board by two inches, pull it closer, and set a timer for three minutes. It’s not dramatic. It’s not inspirational. It’s just enough to keep your body from going into “protect” mode. And somehow, that’s the win.

Safety & when to seek help: don’t push through the wrong signals

This article is for ergonomic self-care and general education only. It does not diagnose or treat sciatica or any medical condition. If symptoms worsen, stop the test. If you have concerning symptoms, seek professional care—especially if anything matches low back pain emergency warning signs.

Safety/Disclaimer (short)

Use stable surfaces, keep knives under control, and don’t do height experiments when you’re rushing or distracted. If a platform shifts, it’s a safety issue first—and a pain issue second.

When to seek help: urgent symptoms vs “schedule an appointment” symptoms

- Seek urgent care now if you have bowel/bladder changes, rapidly worsening weakness, severe numbness in the groin area, or severe unrelenting pain with systemic symptoms like fever.

- Schedule an appointment if symptoms persist, worsen over time, or interfere with sleep and daily function even with conservative changes.

If you’re unsure, err on the side of care. The point of kitchen ergonomics is to make life easier—not to turn dinner into a medical guessing game.

FAQ

What is the best cutting board height for sciatica?

A practical target is a cutting surface that keeps your wrists neutral and reduces forward lean—often close to relaxed elbow height. For many people, raising the board 2–4 inches helps, but the best height is the one that reduces symptoms after prep without creating neck/shoulder strain.

How many inches should I raise my cutting board—2 or 4?

Start with +2 inches. Test for 3 minutes, then assess how you feel 10–60 minutes later. Only move toward +4 inches if back/leg symptoms persist and your shoulders remain calm. Big jumps can trigger the shoulder/neck trap.

How do I know if my cutting board is too low?

Common signs include forward rib drift, low-back bracing, hip hinge fatigue, and symptoms that show up after you finish cooking (standing up from a chair can be a revealing moment). If moving the board closer immediately helps, reach may be the main culprit—not just height.

Why does standing at the counter make sciatica worse?

For some people, prolonged standing and a slight forward lean increase tension through the hips and low back. Add repetitive arm work and bracing for stability, and the nervous system can get irritable. Shorter bouts, stance changes, and reducing reach often help more than “perfect posture.”

Can I use cutting board feet/risers instead of a full platform?

Sometimes, yes—especially for small height changes. The key is stability. Feet that compress unevenly or slide can increase bracing and risk. Always do a push test before using a knife, and re-check periodically because adhesives and rubbers can loosen over time.

Does an anti-fatigue mat help, or can it make things worse?

It can help if it reduces foot discomfort and encourages softer knees. It can make things worse if it slides, curls, creates a trip edge, or makes you feel “stuck” and reluctant to shift positions. Safe, stable footing wins.

Is it better to sit or stand for meal prep with sciatica?

If standing reliably triggers symptoms, sitting (or perching on a high stool) can be a smart modification—especially for longer prep. The “best” choice is the one that keeps symptoms stable and lets you take breaks without feeling trapped (and if you want a desk-life parallel, the logic is similar to a sit-stand schedule for a desk job with sciatica).

What if raising the board helps my back but hurts my shoulders?

That’s a classic sign you’ve overshot height or your board is too far away. Reduce height slightly, bring the board closer, soften elbows, and reassess wrist position. If shoulders keep flaring, prioritize comfort and consider professional guidance.

How long should I chop before taking a break?

A safe default is 3–5 minutes per bout when you’re dialing in a new setup. Take a brief reset: step back, relax shoulders, breathe, and change stance. Duration often matters more than the exact height.

Can counter depth/reach matter more than height?

Absolutely. A board placed even 2 inches too far back can force forward reach and rib drift. Many people feel more relief from bringing the board closer than from adding another inch of height.

Next step: tonight’s 5-minute test (and what to write down)

Let’s close the loop from the beginning: the villain was the quiet lean. Your goal tonight is to remove just enough lean to calm your system—without trading it for shoulder tension.

Tonight’s 5-minute test

- Raise your board by +2 inches using a stable platform.

- Pull the board closer (front-edge rule) so you’re not reaching.

- Set a timer for 3 minutes. Do easy chopping only.

- Stop at 3 minutes. Step away for 10–15 minutes.

- Log how you feel 1 hour after: back, leg, neck/shoulders.

Neutral next action: If it’s better, repeat tomorrow. If it’s worse, reduce height or seek guidance.

Infographic: The 2–4 Inch Riser Range (Elbow-Height Goal)

1) Relaxed elbow level

Target: wrists neutral, shoulders relaxed.

2) Cutting board surface

If too low → you lean. If too high → shoulders hike.

3) Riser range

Start: +2 inches. Tune: +0.5–1 inch based on symptoms.

Tip: If you can’t keep the board close, fix reach first—then fine-tune height.

If you’re deciding what to do next, keep it simple: repeat what works for three days before you change anything again. Your nervous system likes consistency. Your kitchen does too.

And if you want the most conversion-conscious, real-world version of this advice (without buying a single gadget): raise +2 inches, pull the board closer, and cap prep bouts at 3–5 minutes until your body proves it can tolerate more.

Last reviewed: 2026-01-15.